I should start by acknowledging that until the two songs I am about to address became big news I could not have picked Jason Aldean or Oliver Anthony out of a lineup. I had heard of Jason Aldean but could not have named one of his songs. I am confident I had never even heard of Anthony.

I’m a little late to the game in commenting on Jason Aldean’s “Try That In a Small Town” and that is actually by design. I almost jumped in as soon as the song started making headlines and I decided to wait and see if my thinking changed any as the hullabaloo dissipated. It hasn’t, and since Anthony song “Rich Men North of Richmond” is now also getting a lot of attention I decided I would address them both at once.

It is my understanding that Aldean’s song was released a couple of months before the video for the song and that it attracted little attention until the video was released. I think that the images used in the video went a long way toward contributing to the level of attention that the song received—and can specifically be credited with the accusation that the song is pro-lynching—but the song has real issues even if there had never been a video made.

Aldean tried to downplay the possibility that he was endorsing lynching by claiming, rightfully, that there was not a “single clip that isn’t real news footage.” The video, however, was filmed in front of the Maury County Courthouse in Columbia, Tennessee. According to a number of reports, Aldean did not choose the location of the filming and I have no reason to doubt that, but someone did—and it seems unlikely that it was chosen at random. That courthouse was the location of a lynching in 1927. Columbia was also the location of a race riot in 1946.

The song’s lyrics reference “good ‘ol boys, raised up right.” That, too, makes Tennessee a poor choice for filming the video, since southeastern Tennessee was the location for annual gatherings of law enforcement officials known as the “Good ‘Ol Boys Roundup” in the 1980s and ‘90s. Eventually the Department of Justice’s Office of the Inspector General released a 314-page report finding that those gatherings included “shocking racist, licentious, and puerile behavior by attendees occurring in various years. We also found that an atmosphere hostile to minorities — and to women — developed over time because inadequate action was taken by the Roundup’s organizers to appropriately deal with instances of racial or other kinds of misconduct.” The investigation “found substantial credible evidence of blatantly racist signs, skits, and actions in 1990, 1992, and 1995. We also found substantial credible evidence of racially insensitive conduct in 1985, 1987, 1989, and 1993.”[1]

Aldean has said that the song is about “the feeling of a community that I had growing up, where we took care of our neighbors, regardless of differences of background or belief.” He also told a crowd in Cincinnati, shortly after the ruckus about the video began, “I know a lot of you guys grew up like I did. You kind of have the same values, the same principles that I have, which is we want to take our kids to a movie and not worry about some a**hole coming in there shooting up the theater.”

That may be all well and good, but Aldean did not grow up in a small town. Some news reports referenced Aldean’s “native Tennessee” but he is not native to the Volunteer State. He was born in Macon, GA, and grew up splitting time between Macon and Homestead, FL, after his parents divorced. Macon is not a “small town.” Its population exceeded 100,000 for the entirety of Aldean’s growing up years, with Macon usually among the top-five largest cities in the state. Homestead, FL, is actually a small town itself, but given that it is a suburb of Miami, it would be difficult to argue that it fits the definition most people think of when they think “small town”—or that the lyrics of the song have in mind. Aldean now lives in Nashville, a city of nearly 700,000. It would seem that the smallest town he ever lived in was Centerville, TN. Of course, it is not really accurate to say that he lived in Centerville. After all, his residence was over 4,000 square feet and sat on 1,400 acres. Aldean also lived in a home in Columbia for about three years—a home of almost 9,000 square feet with a custom fish tank, a detached bowling alley of more than 4,000 square feet and a 10,000 square foot barn—a property that he sold for some $7+ million. Suffice it to say that Aldean has really never lived in a small town and has not, for quite some time, lived anything like the majority of Americans.

Now that doesn’t mean that he cannot have what one might call small town values. That is, after all, what the song is purportedly about. But like it or not, there is no way around the fact that the song distinctly implies a violent response to undesirable behavior even if it does not say one word about lynching. After all, how else might one interpret “…try that in a small town/see how far ya make it down the road”? It is safe to say that car trouble is not being suggested. The second stanza pretty much threatens a violent response should there be any effort to take away the gun that his grandad gave him. I support the Second Amendment, and I don’t know of any serious effort at gun control measures that would threaten to take away the kind of gun Aldean or most anyone else would have inherited from a grandfather.

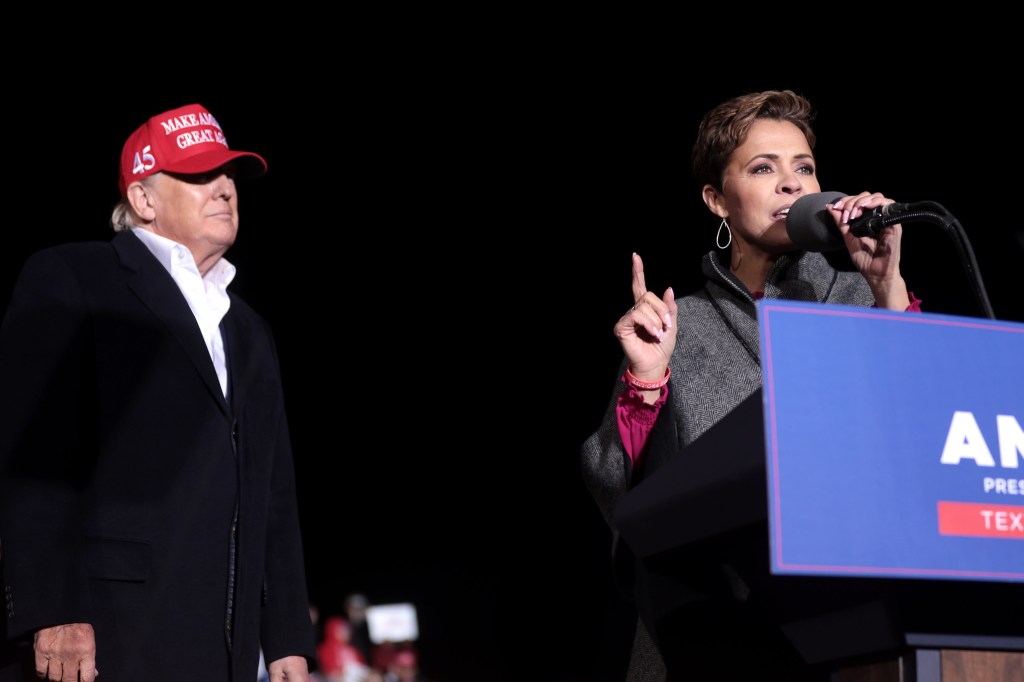

Sheryl Crow was one of many celebrities to speak out against the song. She tweeted that the song is “not American or small town-like. It’s just lame.” The problem, though, is that it isn’t lame. It is tapping into the fomenting sense that violence is the answer that is stoked by Donald Trump and those who think he is the savior of the United States. In February 2016 Trump said, at an Iowa rally, “If you see somebody getting ready to throw a tomato, knock the crap out of them, would you? Seriously. Just knock the hell out of them. I promise you, I will pay for the legal fees.” Three weeks later, at a rally in Nevada, he said of a protester, “I’d like to punch him in the face,” and then, “We’re not allowed to punch back anymore. I love the old days. You know what they used to do to guys like that when they were in a place like this? They’d be carried out on a stretcher, folks.” When, a few weeks later, a Trump support did punch a protester in the face at a Trump rally in North Carolina, Trump called the action “very, very appropriate” and the kind of action we need more of. I could, sadly, go on at length referencing Trump’s tendency to encourage violence. Not surprisingly he has called Aldean’s song “great” and shared on Truth, “Support Jason all the way. MAGA!” Donald Trump, Jr. and Lauren Boebert were among others to publicly support the song. My own governor, Kristi Noem, has strongly endorsed the song, even inviting Aldean to perform on the front lawn of the governor’s mansion. In a video she posted to social media, Noem said that Aldean “and Brittany [his ife] are outspoken about their love for law and order and for their love of this country, and I’m just grateful for them.” She also said that the lyrics represent “the feeling of a community that I had growing up, where we took care of our neighbors. There is not a single lyric in the song that references race or points to it.” Later, on Fox News, Noem said, “All it does is love America, love the flag, love our law enforcement, and it’s everything we should all be proud of.”

Now, Noem did grow up in a small town, graduating from Hamlin High School—in a town of about 6,000. And the majority of South Dakota is what you would think of when you think small town. The problem is that Aldean’s song does not actually say anything about taking care of neighbors or loving law enforcement or loving America. It implies respect for law enforcement but including cussing out a cop or spitting in his face among the behaviors one ought not try in a small town. It also implies love for America by including stomping on our burning the flag as behaviors that one won’t get away with. But nowhere is there any mention of calling law enforcement or supporting law enforcement as they deal with such behavior. Nowhere is there mention of neighbors coming to the aid of a threatened or injured neighbor. While the chorus says “we take care of our own,” the lyrics indicate that such care comes in the form of avenging any wrongs done to them.

There is an obvious question in all of this: what are small town values? What are the characteristics and standards that are seemingly being assumed by Crow and Noem, though reacting oppositely to Aldean’s song? On “Daily Kos” a writer identified as The Choobs wrote in late July that small town values include, or result in, higher rates of gun deaths, suicide, spousal abuse, child abuse, LGBTQ discrimination, drunk driving, vehicular deaths, teenage alcohol use, methamphetamine addiction, cigarette smoking, teen pregnancy and obesity. I don’t know anyone who claims any of those things as values, though, and while there is room for some honest debate over the claim, I am certain that isn’t what anyone in this conversation really has in mind.

Scott LaForest, writing for “Medium” in June, called small town values “the bedrock of all communities.” His article is worth reading—and he gets at what no doubt Crow, Noem and even Aldean all had in mind despite coming at it differently. “Whether it’s rallying together in the face of natural disasters, standing in solidarity against injustice, or pooling resources to help those in need,” LaForest wrote, “the heart of these actions lies in the values fostered in small towns: community involvement, neighborliness, and a deep-seated sense of empathy.” His article elaborates on these and a few others. I don’t have space to give them a full exploration here, but it is not hard to imagine why a community that has high involvement, neighborliness and empathy would be both less likely to experience the behaviors that Aldean’s song references and more likely to address them if they did occur. But by address them I don’t mean with violence, and no matter what Aldean or anyone else may say, there is simply no denying that “try that in a small town” is not an invitation but rather a challenge or even a threat. It is a thinly-veiled assertion that doing so will result in consequences. That’s not liberal interpretation or projecting anything—that’s what “try it” means and anyone who understands the English language and is honest with themselves will acknowledge that.

I am quite willing to grant that there is nothing in the lyrics about race and certainly not about lynching. I am equally willing to grant that Aldean may not have selected the location of the video shoot. But it strains credulity to suggest that another location could not have been chosen. After all, Columbia is almost 50 miles from Nashville; how many other courthouses are there between Nashville and Columbia—or within a 50-mile radius of Nashville? Centerville, for example—the town outside of which Aldean had his 1,400-acre spread, is home to the Hickman County Courthouse and is 60 miles from Nashville. A 2020 article in the Williamson Herald, a newspaper out of Franklin, TN, indicates that there are 95 county courthouses in Tennessee. The one in Columbia is included among the eight that the author says are the state’s most attractive, but that leaves seven more even if one wanted to argue that aesthetics was part of the reason the Maury County Courthouse was chosen. One of those eight is the Cannon County Courthouse in Woodbury, 58 miles from Nashville. Another is the Montgomery County Courthouse in Clarksville, TN—53 miles from Nashville. The Giles County Courthouse in Pulaski is just 73 miles from Nashville.

There are indeed small-town values that could and should be celebrated and about which songs could be, and have been, written. This particular song, however, has connotations and implications that are not anything that should be celebrated. Having said that, there are many songs that have lyrics and messages that should not be celebrated and many of them are far more offensive and blatant than “Try That In a Small Town.”

One last note before moving on. Aldean graduated from Windsor Academy, a Christian school in Macon, in 1995. There is no evidence that the school has any issue with the lyrics or the video for “Try That In a Small Town,” and apparently the school is more than happy to tout Aldean’s affiliation with the school, including his picture and a brief biographical comment on its website as part of “Our Team,” a section in which everyone else pictured is a current member of the school’s faculty and staff. It’s too bad that the school has not seen fit to issue a statement clarifying why the song does not represent the kind of values that we should be seeking to embrace.

Now, what about Anthony Oliver’s “Rich Men North of Richmond”? Well, it’s become an overnight viral sensation. Sadly. Political protest songs are nothing new and neither are lyrics that portend to speak for the downtrodden, the working class and the politically ignored. But this song has very little going for it for anyone who gives it serious consideration. It doesn’t have much in common with Aldean’s song other than the inclusion of profanity, which has become increasingly—and depressingly—common. What the two songs do have in common is the base to which they appeal, despite Oliver claiming that he is a political centrist. But when Marjorie Taylor Greene and Kari Lake both come out in support of the song, you can quickly identify the audience with which is resonates.

The song starts with these lyrics: “I’ve been sellin’ my soul, workin’ all day / Overtime hours for bullsh*t pay / So I can sit out here and waste my life away / Drag back home and drown my troubles away.”

Well, hmmm. I am not sure how working full time equates with selling one’s soul. Usually selling your soul implies doing something that is wrong, or morally dubious at best, in order to achieve a goal or obtain a want. By that definition, Anthony would be suggesting that not working is what he desires but he has to work in order to achieve what he wants. In Facebook posts, Anthony has discussed the lousy wages he earned working third shift in a paper mill. But apparently he also dropped out of high school. Sometimes we do indeed reap what we sow. We’ll come back to the not working shortly, but if he is working—not just full-time, but overtime—what is he doing that for? What goal is he trying to reach? Apparently not much, since the lyrics indicate that he is doing it so that he can sit “out here” (wherever that may be) and waste his life, drowning his troubles away. Though is doesn’t say so explicitly, one can easily imagine that drowning of troubles after dragging back home to involve copious amounts of alcohol.

The next lines say, “It’s a damn shame what the world’s gotten to / For people like me and people like you / Wish I could just wake up and it not be true / But it is, oh, it is.” This is a line that makes little sense since the listener is left wondering who exactly “people like you” is and what precisely it is that Anthony would like to not be true. Presumably, based on the chorus, Anthony would prefer a world with a lower tax rate, since it goes like this:

Livin’ in the new world / With an old soul / These rich men north of Richmond / Lord knows they all just wanna have total control / Wanna know what you think, wanna know what you do / And they don’t think you know, but I know that you do / ‘Cause your dollar ain’t sh*t and it’s taxed to no end / ‘Cause of rich men north of Richmond.

There is seemingly unanimous agreement that the “rich men north of Richmond” are the politicians in Washington, D.C, though it could possibly refer to the wealthy D.C. suburbs, too. Not that I cannot relate to wanting to keep more of my money, but current U.S. tax rates for someone making the kind of money Anthony sings about are not all that high historically speaking. BUt high taxes is not the only thing that Anthony thinks they are wrong about. The song continues:

I wish politicians would look out for miners / And not just minors on an island somewhere / Lord, we got folks in the street, ain’t got nothin’ to eat / And the obese milkin’ welfare.

Well, God, if you’re 5-foot-3 and you’re 300 pounds / Taxes ought not to pay for your bags of fudge rounds / Young men are puttin’ themselves six feet in the ground / ‘Cause all this damn country does is keep on kickin’ them down.

One cannot help but ask how Anthony would like politicians to look out for miners. Does he want less emphasis on “green energy” or more safety protocols for mining? Or does he think miners should make more money? It would be hard to imagine more government oversight and safety requirements and benefit funds than there are already in place for current and former miners. And miners are not generally low-income earners, either. In fact, the median salary for a coal miner is almost exactly the same as the median salary for all U.S. workers. Many coal miners don’t go to college not because they couldn’t but because they do not need to. ABC News ran a story in 2010 touting the ability of a beginning coal miner in Appalachia to earn $60,000 or more—and according to Mint, $70,000 is still the average salary of a U.S. coal miner.

What is clear is that whatever it is that Anthony wants for miners, it is more important to him than protection for sexually-abused minors—a commentary that is truly sad. Of course, it also seems out of place for Taylor Greene to endorse the song with this lyric since she is such an adherent of QAnon and the thus-far unproven rumors that there is a vast pedophile ring in existence among the world’s wealthy elite. Suggesting that too much attention is paid to minors on an island somewhere doesn’t fit with the QAnon narrative.

The next few lines don’t make much sense, either. Anthony goes from lamenting that there are folks in the street without food to chastising the existence of welfare programs that provide food for those who cannot afford it. Now, it is clear that by referencing the “obese milkin’ welfare” and the grossly-overweight person eating fudge rounds that Anthony thinks that those receiving what is commonly known as food stamps are often abusing the system.

According to a story on NBC’s “Today,” Anthony acknowledges struggling with mental health and drowning it with alcohol. He said that is sad to see a world in which everyone is fighting with each other. Chastising those on welfare seems an odd way to try to bring about peace—especially when one listener commented on X that the line about a 5-foot-3 person weighing 300 pounds is the “best lyrics in the history of music.”

Anthony drew lots of attention for selling out a concert he will be doing in Farmville, VA, in three minutes. News reports indicate that people are driving from as far away as Ohio and New Hampshire to attend. I cannot help but ask, “Why?” Anthony is a flash in the pan, the current unknown-makes-it-big story that most everyone seems to love. But the reality is that while he might have a decent voice, it’s a lousy song. Anthony has been open about saying that he wrote it while suffering from poor mental health and depression. I do not intend this to be funny, and certainly not to mock the reality of depression and mental health challenges, but that might explain why the song doesn’t make sense.

As this post is already rather long, I will not go further into disingenuous lyrics of the song in terms of the political arguments it attempts to make. Others have done that already, including Kenan Malik in The Observer and Eric Levitz in The Intelligencer. Jamelle Bouie, in an opinion piece for The New York Times, sums up well what I think of Anthony’s politics when he writes, “For my part, I can’t help but think there’s something ironic about the fact that, despite sitting close to this history, the latest populist voice to come out of the commonwealth has chosen, in the end, to give comfort to those with the boot on his neck and scorn to those who might try to help lift it.”

The article in response to Anthony’s song that perhaps struck me the most was Hannah Anderson’s piece for Christianity Today. Anderson takes strong issue with Anthony’s lines about welfare, saying that she was instantly reminded of the time when her family was on food stamps and the shame that she felt about that reality. Anderson rightly makes points about the judgment that others so often place on those receiving government assistance and about the way that those on assistance often feel about it.

However, she has several missteps in her column, as well. For one, she uses the term “food insecurity” in a way that I would consider inaccurate, despite the fact that it is consistent with the way that the U.S. Department of Agriculture uses it. That, however, is mostly a matter of semantics and opinion. Anderson wisely points out that she and her husband were both college-educated at the time that they were on food stamps, and that her husband was employed, highlighting the fact that not all of those on government assistance programs are just moochers unwilling to work. She does not acknowledge, though, that some of the reasons why her family could not make ends meet were of their own doing. Anderson states that she was not employed; rather, she stayed at home with their children. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course, but she references the fact that once they had their third child they could no longer make her husband’s salary cover their needs. (Her husband was a pastor and I’ll come back to the church’s culpability in a moment). Is it responsible to have another child if someone knows they will not be able to afford to care for that child? I would suggest that it is not. Once they qualified for SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the federally-funded program commonly referred to as food stamps), Anderson said the money that they had previously used for food was “relocated” to pay for things like gas and preschool for her daughter. Preschool? I’m sorry…I thought Anderson was a stay-at-home mom? Why would she and her husband pay to enroll her daughter in preschool if they could not afford food? That too, was irresponsible.

Anderson also commented that there were limits to what SNAP would cover, specifically mentioning that paper products, toiletries and cleaning supplies were not included. Well, that’s good. They shouldn’t be covered. After all, they are not nutritional items and SNAP is decided to ensure access to proper nutrition. SNAP also does not cover alcohol, tobacco or pet foods. Neither will it cover food that is hot at the point of sale or vitamins.

That last one doesn’t seem to make much sense, particularly given that SNAP will cover snack foods. It is the snack foods coverage that gives rise to Anthony’s line about fudge rounds, the chocolate frosting between two chocolate cookies made by Little Debbie. While they’re tasty, they are not nutritious, and I absolutely can relate to the frustration of seeing someone purchase junk food with government assistance funds. I don’t approve of the body shaming that is clearly included in Anthony’s lyric, but I share the opinion that fudge rounds—and snack foods in general—ought not be covered by SNAP.

Anderson does rightly call out the casually-used language of some within the Church that uses too wide a stoke when condemning government assistance programs. Should there be work requirements for welfare recipients? Absolutely. But are there some people who are working hard and still struggling to make ends meet? For sure.

That is, by the way, where the Church should come in, and that is actually the most offensive part of the story that Anderson tells. Her husband, at the time that their family was receiving SNAP benefits, was a pastor. His salary was only $28,000. Anderson does not say whether their housing was provided and she does not say how long ago this was, either; she references being 30 years old but there is no indication of when that was. She said that they asked the church board for a raise in order to better provide for their family but were given half of what they asked for and were told that social services were available. Unless the church could honestly not afford to pay any more, this is appalling. A church has an obligation—a biblical responsibility—to provide for its pastor. If the church truly could not support the Andersons full-time, then Anderson’s husband should have sought a second job and become bi-vocational or sought some other way to provide for his family if that was where he believed God wanted him to serve, but the fault in this story lies with the church board. Directing someone within their congregation to utilize government assistance should never be the first reaction of a church body; the congregation should care for its own—and certainly for its pastor.

Anderson is correct when she writes, “The price of accessing food through SNAP or a church food pantry must not be the poor’s dignity and self-worth.” I can relate to the shame she felt and the desire to keep it under wraps that their family needed government help. When I was a young teenager my father left a well-paying job to enroll full-time in Bible college. He worked at the college, too, but our family’s needs were beyond his income and we qualified for free lunches at school and WIC benefits for my younger sisters. Later, as an adult, I lost my job suddenly and experienced the sudden change in circumstance that many people experience when losing a job. I went from taking students to volunteer at a Salvation Army shelter to serve meals to, not too many weeks later, going to a church food pantry to get some food when the pastor extended to us the offer. It was humbling. We never had to accept any government assistance at that time beyond the unemployment payments I received, but it did cause me to rethink the judgment that can easily come into one’s mind—and be reflected in one’s attitude—when we see someone not able to provide for themselves or their family.

So, Mr. Anthony, I agree—fudge rounds should be out. But SNAP and similar government programs do serve a legitimate purpose—one too often neglected today by the Church. And no one who legitimately needs such government services should ever be scorned or belittled. The odds are good that they hate needing it already; the last thing they need is for you or me to condemn them for that need. But most importantly, it is a sad day when professing believers cannot even see that “love your neighbor as yourself” would certainly include ensuring that your pastor’s family can afford to eat.

Ultimately, these two songs are getting a lot of attention–much ado, one might say. In the case of the Aldean song, it is not much ado about nothing because there is, and should be, a legitimate debate over the kinds of things the song is about. While he is correct that the behaviors he sings about should not be tolerated or go without consequence, he is wrong to suggest or imply that they should be dealt with by some kind of vigilante justice. In the case of the Anthony song, though, I think it really is much ado about nothing. After all, the song has no discernible point.

[1] https://oig.justice.gov/sites/default/files/archive/special/9603/exec.htm

Photos: YouTube captures.